Visual Signaling in MLB

Photograph by Andy Bertelsen

Author's Note

This paper represents my original conceptual work, shaped by my dual perspective as both an athlete getting back into the sport of baseball and an emerging anthropologist. I employed generative AI tools (ChatGPT) during the drafting and revision process of this paper to refine language, enhance transitions, and finally simulate structured data for visual analysis. All theoretical interpretations, methodological choices, and citations were selected through critical engagement with my current use of anthropological theory and grounded in personal, field-informed insight. I believe that using AI in this context reflects responsible scholarly practice in the digital age, offering support in the writing process while preserving the depth of interpretation and cultural insight that define classical anthropological work.

Abstract

This study is grounded in applied anthropology and draws from player interactions, embodied perception, and the symbolic structure of performance. It examines how high-contrast, customized gear alters perceptual awareness and behavioral rhythm in elite athletic settings. Using a hybrid methodology that combines participant observation with an AI-generated data set of 50 simulated plate appearances, the analysis identifies that, instead of following a predictable pattern, the disruption caused by neon gear leads to uneven shifts in performance, unsettling the dynamics between pitcher and batter. Rather than producing strategic advantage, its effect is better understood as a source of instability within this ritualized exchange. This disruption interrupts the visual rhythm that performance depends on. The study demonstrates how anthropological methods, paired with data visualization, can uncover subtle behavioral patterns often overlooked in institutional sport.

Understanding Visual Disruption in Baseball

In elite performance settings like Major League Baseball, subtle visual cues can alter behavioral patterns by disrupting psychomotor coordination. Research in color psychology suggests that neon sportswear affects not just visibility, but also perceptions of status and confidence (VenuEz, 2023). Findings from Vanderbilt University similarly indicate that neon gear projects elite potential, reinforcing self-perception while signaling dominance to opponents and spectators (Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management, 2013), thereby transforming visual presentation into a psychological tool that can subtly alter competitive dynamics.

This paper explores how visually expressive gear functions as a form of symbolic signaling capable of subtly disrupting pitcher performance. Drawing from symbolic interactionism, sensory anthropology, and ritual theory including foundational work by Victor Turner (1969) and Marcel Mauss (1973). This study uses AI-assisted simulation to examine how visual presentation reshapes the perceptual field in which elite athletes operate. Rather than interpreting performance solely through biomechanical or psychological frameworks, this research situates the baseball field as a ritualized cultural space. It explores how visual aesthetics contribute to perceptual disruption and behavioral volatility. The findings suggest that neon gear does not enhance dominance but instead introduces instability by interfering with rhythm and focus. This challenges conventional performance narratives and underscores anthropology’s ability to expose hidden influences often ignored by traditional sports science.

Despite the centrality of perception in elite sport, the behavioral impact of gear-based visual signaling remains largely unexamined. Understanding these effects has implications not only for player performance, but also for how leagues regulate appearance and maintain competitive integrity.

This project also emerges from my experience as a competitive player returning to the sport as an adult. In navigating the modern commercial landscape of protective gear, I became attuned to the performative role that visual presence now plays. Color, contrast, and branding are no longer just design choices. They have become central to how players present themselves and influence the visual rhythm of the game. This shift creates a psychological edge before any action even begins. What started as a personal curiosity about distraction grew into a deeper anthropological inquiry. Certain gear disrupted my rhythm both on the field and in the dugout, where neon equipment often sparked conversation among players. These moments made it clear that gear is not just functional, it also shapes how players perceive each other and how performance unfolds. How does color shape perception, and how does perception, in turn, alter performance?

Grounded in the intersection of field experience and theoretical reflection, this study adopts an applied anthropological lens to examine symbolic disruption in elite sport. It asks not only whether visual signaling affects athletic outcomes, but how it reshapes the sensory and cultural logic that governs the game. This framework guides the methodology that follows, which investigates whether gear-based visual signaling, particularly in its most visually disruptive forms, produces measurable shifts in behavior on the mound and in the batter’s box.

How Ritual, Identity, and Symbolism Shape the Game

To understand the behavioral consequences of gear choice in Major League Baseball, one must view the sport not merely as a competitive structure but as a cultural performance space shaped by ritual, signaling, and institutional codes of identity. Ritual refers to the repeated and stylized acts that organize the rhythm and flow of the game. These include pregame routines, mound visits, and home run celebrations, which carry symbolic meaning and reinforce shared expectations among players and spectators. Signaling involves the expression of intention, affiliation, or persona through visible actions and bodily cues. Examples include adjusting one’s stance in the batter’s box, making the sign of the cross, or spitting after an off-speed pitch is the batter’s first strike. These behaviors influence tempo, establish presence, and communicate nonverbal information within the game. Institutional codes of identity are the visual and behavioral standards set by the league. These include guidelines on jewelry, sponsorship visibility, and the presence or absence of protective gear. Such rules define how individuality is managed, permitted, or constrained within the collective performance of professional baseball. These categories of behavior, including ritual, signaling, and identity codes, can be further illuminated by theoretical perspectives that help explain how meaning is constructed, sensed, and performed on the field.

Drawing from symbolic interactionism, sensory anthropology, and performance theory, this study approaches gear as more than equipment. Symbolic interactionism helps interpret gear as a visual language of identity and status, read and responded to in real time by players and audiences. Sensory anthropology views gear as part of the athlete’s embodied environment, shaping perception through physical awareness and affective responses during high-stakes play. Performance theory adds that gear plays a role in managing presence and rhythm, serving as a psychological device within competitive settings. Together, these frameworks position gear as an expressive artifact and behavioral catalyst.

Neon-colored gear, including arm sleeves, batting gloves, elbow guards, and leg guards, is often seen as a protective tool or stylistic choice. Yet for many players, particularly those from Latin American backgrounds, vibrant gear reflects cultural aesthetics rooted in regional identity and personal expression. These visual elements are not merely decorative; they serve dual purposes as symbolic disruption on the field and as extensions of off-field identity. In tightly regulated environments like MLB, this form of expression becomes a subtle act of self-assertion.

Major League Baseball’s own regulations reinforce the limits of this expression. Rule 3.03 mandates that all players on a team wear identical uniforms in color, trim, and style, explicitly prohibiting personal modifications. Rule 3.07(a) further restricts visual choices by banning gloves that are white, gray, or considered distracting, and disallowing reflective or contrasting materials. These policies show that even officially sanctioned gear remains subject to visual control. Uniformity and cohesion are institutional priorities, and any display of individuality must occur within a defined aesthetic boundary.

Victor Turner’s (1969) theory of ritual performance helps contextualize this dynamic. Turner argues that structured roles and repeated actions, performed within bounded environments, produce meaning and transformation. Within this lens, the pitcher and batter exchange becomes a ritualized encounter shaped by rhythm, repetition, and symbolic roles. Expressive gear acts not only as a personal signal but as a boundary marker within that shared performance. These routines are not just functional; they carry symbolic weight, turning the field into a site of negotiated meaning.

This paper situates neon gear within the broader matrix of identity, ritual, and commercial culture in Major League Baseball. Rather than treating visual disruption as a purely strategic advantage, this framework interprets it as a cultural artifact that is expressive, marketable, and behaviorally impactful. In this view, gear extends beyond branding. It becomes a sensory variable that subtly reshapes in-game perception and disrupts behavioral rhythms.

These symbolic choices align with what Marcel Mauss (1973) described as techniques of the body, referring to culturally learned movements, gestures, and forms of dress. Within this framework, gear selection becomes a form of bodily communication, a grammar of presence, confidence, and belonging that expresses both cultural identity and institutional affiliation. The batter is not simply an individual executing skill, but a cultural actor participating in a ritualized performance constrained by league codes and shaped by social meaning.

It is within this negotiated visual space that subtle disruptions emerge. These are the disruptions this study aims to identify and analyze. The following methodology section outlines how this symbolic framework was translated into a simulated observational model designed to test whether visual signaling, particularly through neon gear, has measurable effects on pitcher behavior.

How the Study Was Designed and Simulated

This case study uses a hybrid methodology that combines observational anthropology with AI-assisted simulation. The dataset was synthetically generated using real-world MLB matchups as structural templates, while pitch outcomes and player behaviors were simulated to model symbolic and sensory disruption under controlled conditions, with neon gear serving as the primary visual variable. This approach, which can be described as simulated ethnographic modeling, enabled rapid prototyping of the research framework and allowed for theoretical testing without the logistical constraints of live data collection. While the catcher contributes to the visual environment, variables related to catcher gear were excluded in order to isolate the batter’s appearance as the primary visual stimulus under observation.

The dataset consists of 50 simulated plate appearances, evenly split between batters wearing neon gear and those in traditional or neutral attire. Each entry was coded for variables including game date, batter and pitcher identity, pitch type, location zone, pitch velocity (mph), and outcome (e.g., strikeout, hit, walk). Visual interference was tracked through binary indicators such as whether the pitcher missed the intended location or whether the batter made hard contact. These indicators were used to infer symbolic or perceptual disruption, treated as potential behavioral responses to visual signaling within the at-bat sequence.

While the data are simulated, their structure mirrors that of MLB’s Statcast system and tools like Baseball Savant. Player matchups were chosen from recognizable major league athletes to enhance realism. The study does not aim to produce empirical generalizations, but rather to test a symbolic and behavioral hypothesis within a structured model of sensory disruption. As such, this reflects an applied anthropological approach, using synthetic data to examine how cultural behavior and perception interact with ritualized performance and symbolic meaning in institutional settings.

Future research could expand the dataset, incorporate live Statcast metrics, or conduct controlled trials with amateur and semi-professional players. Adding qualitative variables such as observed body language, timing disruptions, or player-reported focus could also reveal more nuanced dimensions of visual signaling. For the purposes of this portfolio, however, AI-generated simulation provides a pragmatic method for exploring how visual signaling may influence elite motor performance, even when those effects are not consciously perceived.

What the Visual Data Shows About Disruption

Professional players like Randy Arozarena, Fernando Tatis Jr., and Julio Rodríguez exemplify a visually expressive style that merges performance, personality, and cultural identity. Arozarena, in particular, is known not only for his athletic skill but for the way he visually narrates his presence, through colorful gear, celebratory gestures, and expressive routines that assert individuality within a heavily regulated system. Even players who adopt a more restrained aesthetic still convey identity through body language, tempo, and gear choices. These visual elements are not simply theatrical; they signal cultural pride and challenge institutional expectations of uniformity. High-end, customized protective gear, often shaped by sponsorships, allows players to fuse function with symbolic expression, creating what might be understood as a personal visual signature. In this sense, all players participate in a symbolic economy where aesthetic choices become extensions of identity. As the technology for protective gear advances, so does the potential for individualized expression, reinforcing the gear aesthetic as a dynamic medium of self-representation.

Tim Ingold’s (2000) work on environmental perception offers a useful frame for understanding how visual expression functions beyond surface-level distraction in baseball. Ingold argues that perception is not passive or purely visual, but embodied—shaped by how individuals move through, sense, and respond to their surroundings. In the context of pitching, this suggests that the batter’s gear is not simply a visual object but a sensory presence that enters the pitcher’s perceptual field. For example, bright neon sleeves, irregular color contrast, or reflective elements may momentarily distort spatial rhythm, draw the eye off-center, or subtly interfere with the timing of a delivery. These effects are not always conscious, but they contribute to what Ingold might frame as an active process of moving through and attuning to the environment, particularly under the temporal and spatial pressure of high-stakes performance. The batter’s gear becomes part of the visual architecture the pitcher must navigate, shaping how space, rhythm, and movement are perceived in real time. In this way, perception is not merely a matter of looking, but of moving through and adjusting to a visually charged encounter.

This section presents five visualizations that illustrate the central claim of this study: that neon gear contributes to measurable behavioral disruption in pitcher performance. Each chart is derived from the simulated dataset and is accompanied by symbolic interpretation, revealing how visual interference may reshape pitcher–batter dynamics in subtle but significant ways.

These visualizations, which map pitch location, miss rates, and hard-hit outcomes, are not just statistical outputs; they can be read as cultural texts. As Sarah Pink (2009) argues in her work on sensory ethnography, data must be understood not as neutral recordings but as situated reflections of lived and embodied experience. Pink emphasizes that sensory knowledge, including how people see, hear, feel, and move, cannot be separated from the environments in which it is produced. In the context of baseball, this means that a missed pitch or hard contact is not just a performance metric but a trace of perceptual tension, of attunement or disruption under pressure. As interpreters of data, we too participate in this process. We do not just observe the outcomes; we feel their rhythm, their spatial logic, and their symbolic weight. The charts are not simply outputs of simulation. They are artifacts of interaction that reveal how gesture, color, and visual presence operate within a tightly choreographed sensory world.

These charts translate cultural and sensory expression into visual form, offering insight into how aesthetic choices may influence in-game behavior. Framed anthropologically, gear functions not just as protective equipment but as a communicative device embedded in the dynamics of ritual, perception, and performance.

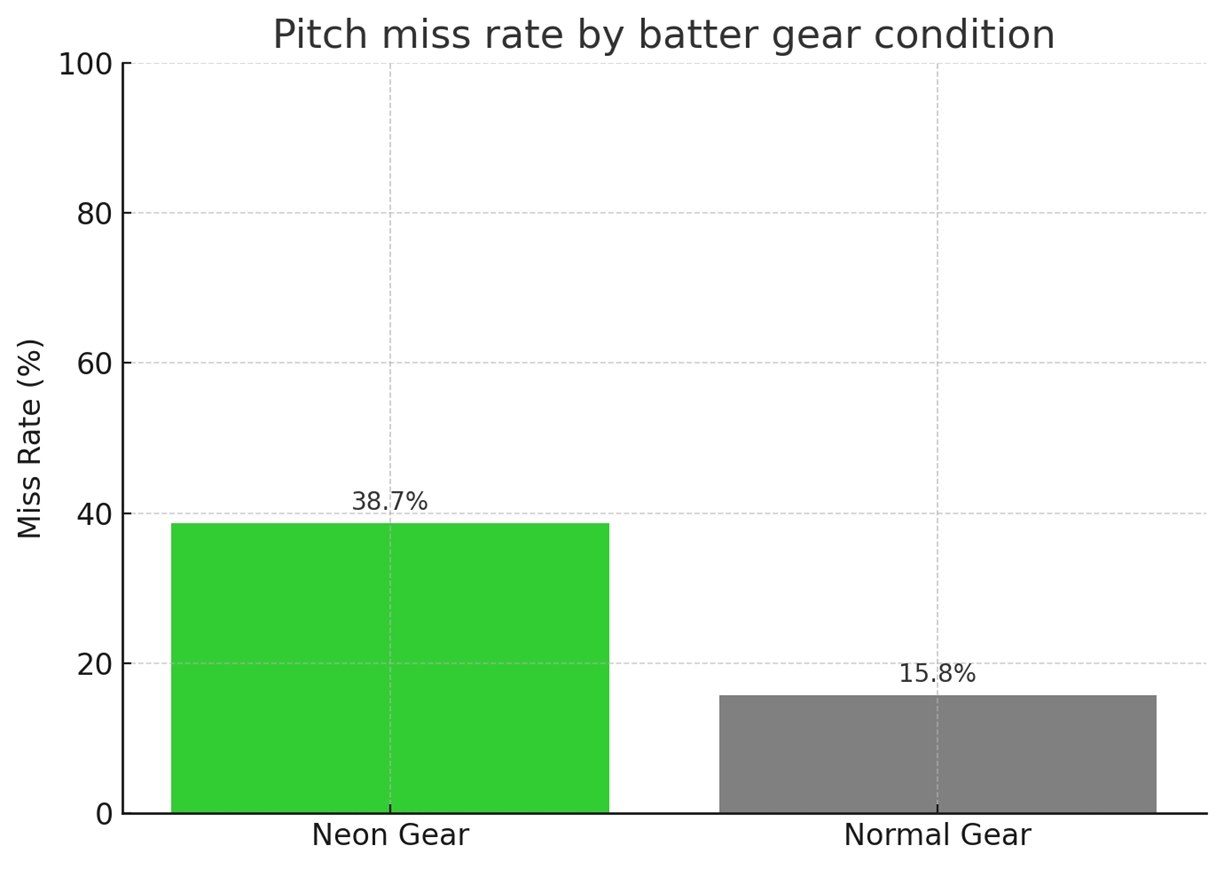

Chart 1: Increased Location Misses Under Visual Disruption

Chart 1 shows that pitchers missed their intended pitch location at a significantly higher rate when facing batters wearing neon gear compared to those in traditional or neutral attire. This suggests that high-visibility gear may subtly interfere with a pitcher’s rhythm or spatial targeting process. However, these disruptions did not consistently result in improved offensive outcomes. Many of the off-target pitches, defined here as those that missed the intended strike zone location, still led to strikeouts or weak contact, including groundouts, lineouts, and pop-ups. The core insight here is not advantage but instability. Neon gear appears to introduce perceptual volatility that affects command without guaranteeing success for the batter.

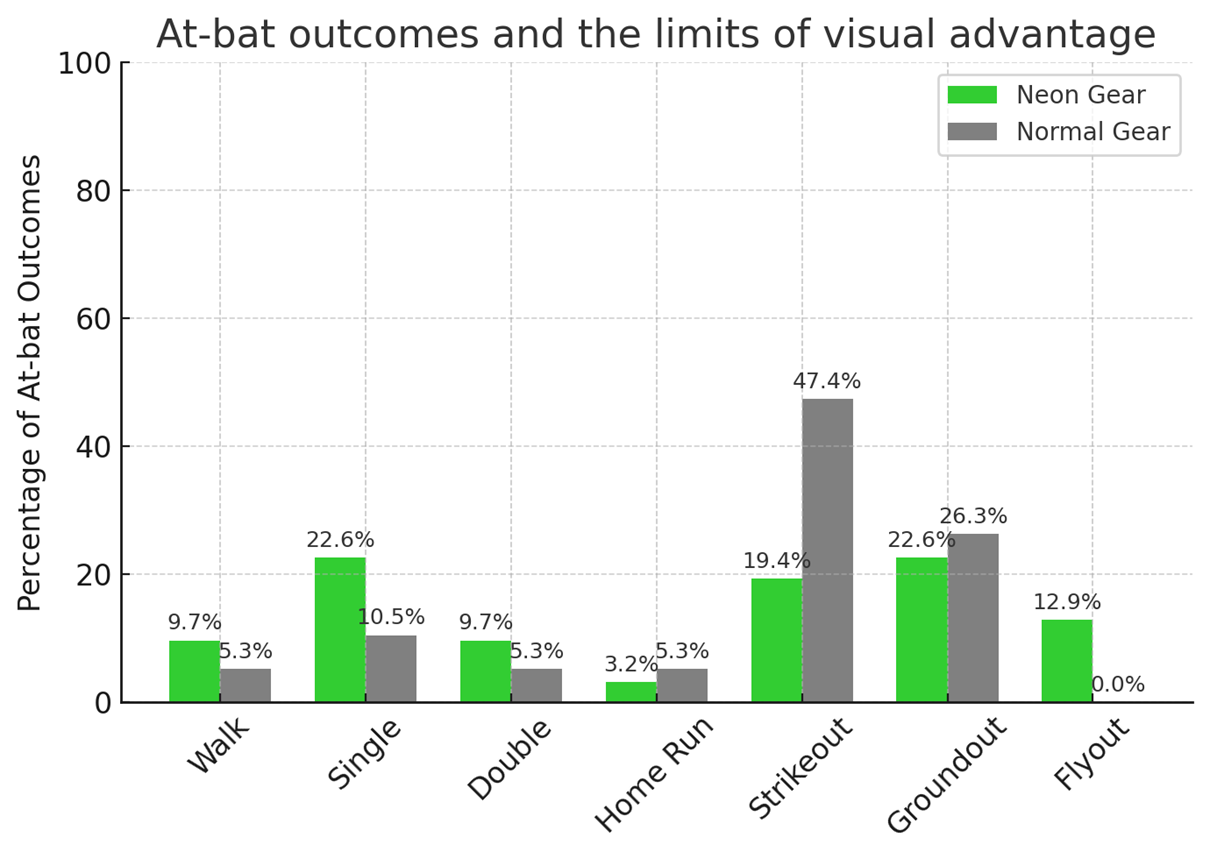

Chart 2: At-Bat Outcomes and the Limits of Visual Advantage

Chart 2 compares the percentage of final at-bat outcomes between neon-wearing batters and those in traditional or neutral gear. Batters wearing neon gear recorded a higher percentage of walks and a lower percentage of strikeouts, suggesting that pitchers facing visually expressive opponents may experience greater difficulty locating pitches consistently. This observation aligns with the findings in Chart 1, which showed elevated miss rates under neon conditions. However, this apparent loss of command did not translate into more hits or hard contact. Batters in neon gear still struggled to capitalize on errant pitches, with most outcomes resulting in weakly hit balls or routine outs.

The chart underscores a subtle but important dynamic: neon gear may destabilize the pitcher’s control, but it also introduces uncertainty for the batter, who must adjust to unpredictable pitch trajectories. From an anthropological perspective, both players are operating within a shared perceptual environment shaped by visual signaling. Rather than a clear competitive advantage, the result is a form of mutual disruption—a shifting sensory landscape that alters timing, rhythm, and perception for both sides of the exchange.

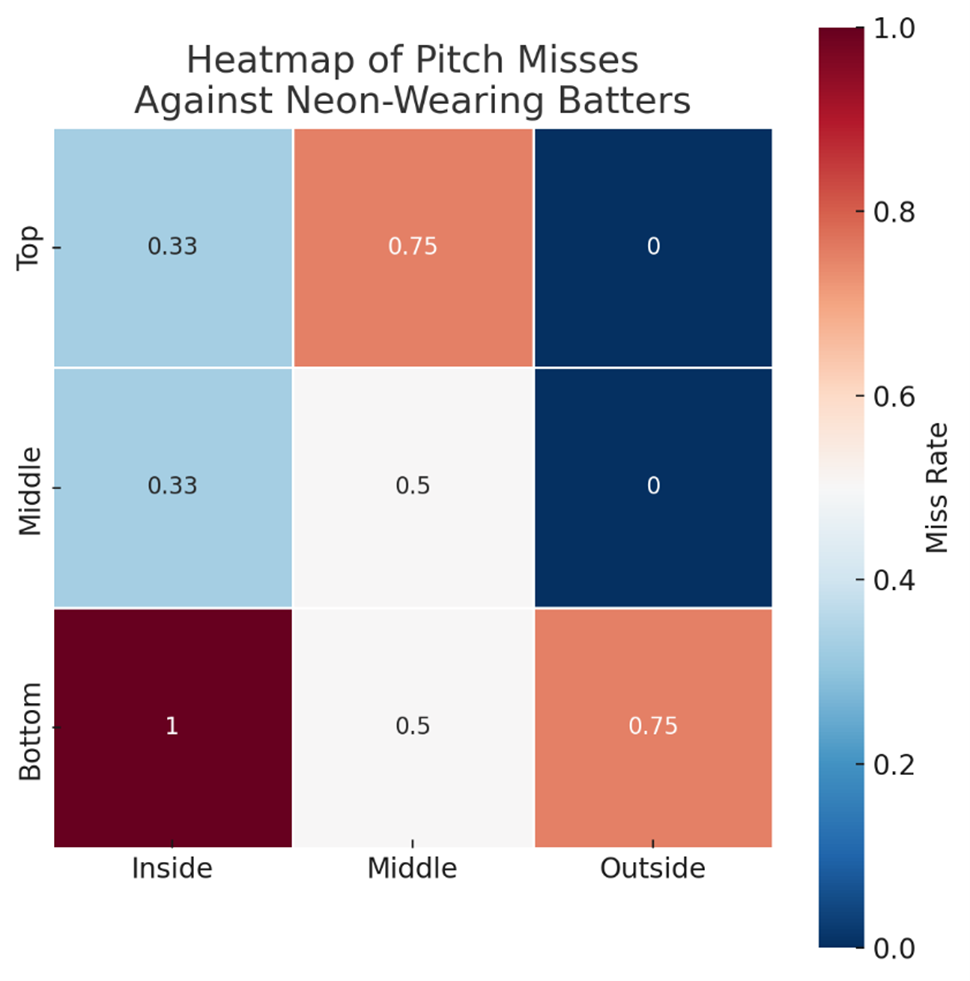

Chart 3: Heatmap of Pitch misses Against Neon-Wearing Batters

Chart 3 presents a heatmap of pitch misses against batters wearing neon gear, revealing an uneven and spatially disorganized distribution. Rather than missing in predictable or strategically cautious zones, such as low and away or just off the edges, misses appear scattered across the central and outer-middle regions of the strike zone. This irregularity suggests more than isolated lapses in control. It points to a breakdown in rhythmic targeting, where the pitcher’s internal timing and sequencing are disrupted by visual stimuli. The outer-middle and middle-up quadrants, typically high-risk areas for hard contact, show elevated miss rates, indicating that the disruption affects not only accuracy but decision-making.

Viewed anthropologically, this pattern reflects a shift from controlled execution to adaptive improvisation. Neon gear functions here not as a distraction in the conventional sense, but as a destabilizing visual element embedded in the pitcher’s perceptual field. In these moments, command becomes less about deliberate placement and more about compensating under sensory pressure. The heatmap transforms into a spatial narrative of symbolic interference, revealing how aesthetics can unsettle the embodied routines of elite performance.

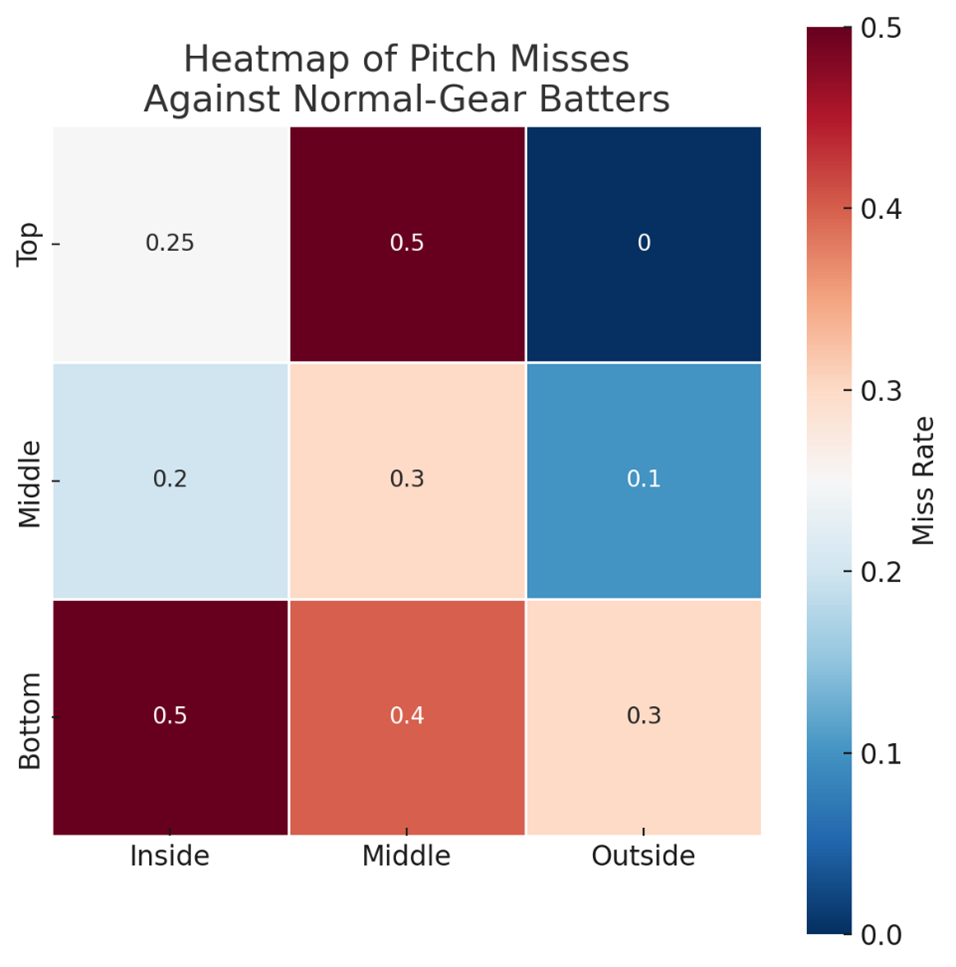

Chart 4: Heatmap of Pitch Misses Against Normal-Gear Batters

In contrast to the disrupted spatial pattern shown in Chart 3, Chart 4 presents a more balanced and strategically coherent distribution of pitch misses when pitchers faced batters in traditional or neutral gear. The heatmap displays a cooler, more symmetrical spread, with misses largely confined to low and outer edges—areas that align with conventional pitching strategy aimed at minimizing hard contact. This spatial discipline suggests that, in the absence of high-visibility visual stimuli, pitchers are better able to execute deliberate sequences and maintain rhythmic control.

Whereas Chart 3 revealed instability shaped by visual excess, this chart reflects a return to perceptual clarity. Pitchers appear more attuned to their environment, less reactive, and more composed in their decision-making. From an anthropological perspective, the exchange between pitcher and batter unfolds here with ritualistic integrity. The absence of symbolic interference restores a shared spatial logic rooted in skill, habit, and embodied familiarity. In this sense, control is not merely technical, but perceptual—and it thrives when the visual field remains culturally and aesthetically stable.

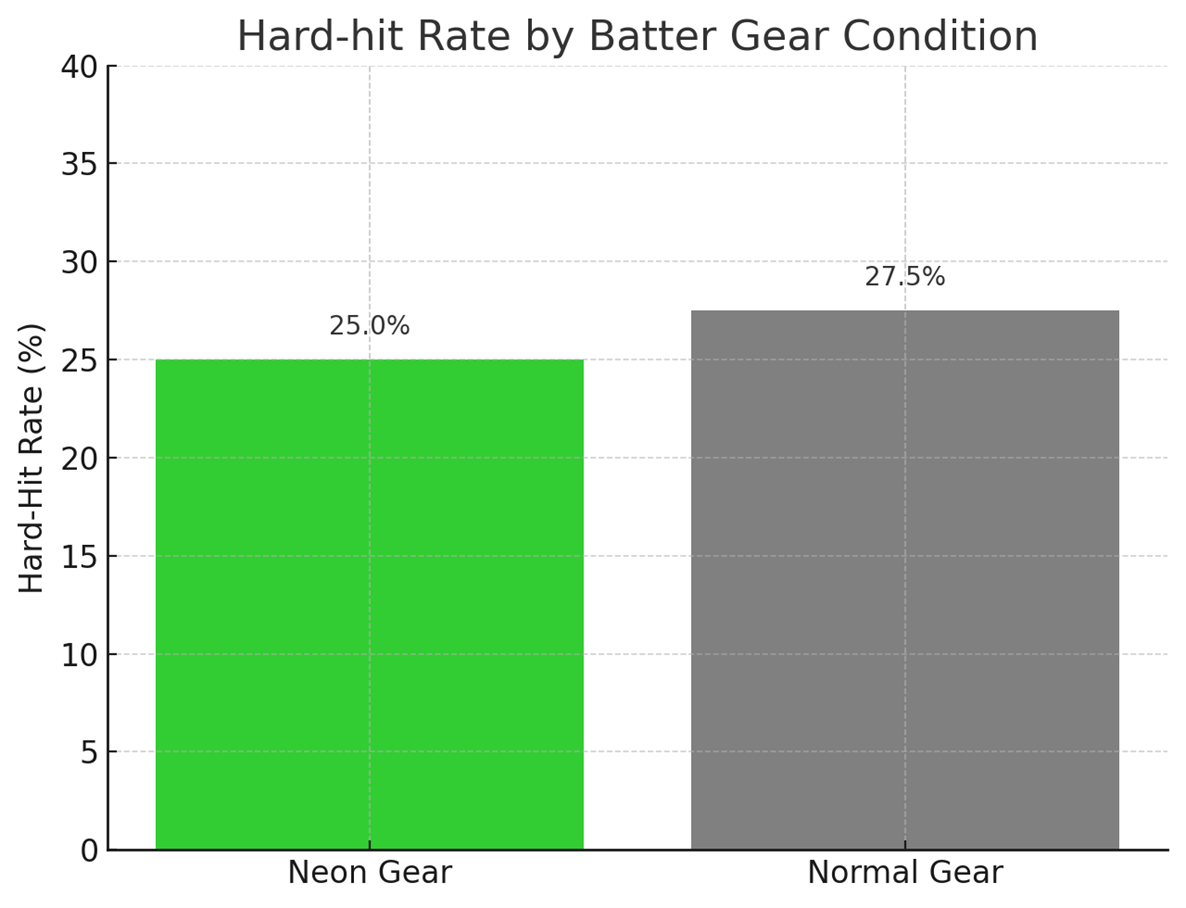

Chart 5: Hard-hit Rate by Batter Gear Condition

Chart 5 reveals a striking and counterintuitive pattern: batters wearing traditional gear produced a higher hard-hit rate than those wearing neon, despite earlier evidence that neon gear disrupts pitcher command. This is not a trivial difference—it suggests that while neon gear may destabilize the pitcher’s control, the resulting volatility appears to work against the batter as well. Hitters in neon must contend with inconsistent sequencing, altered tempo, and degraded visual cues, all of which undermine their ability to time and square up the ball.

This finding reinforces the study’s central claim: visual disruption does not guarantee competitive advantage. Instead, neon gear generates mutual instability—interfering with both the execution of the pitcher and the perception of the batter. What appears on the surface as expressive confidence may, in fact, fracture the internal rhythms required for clean, high-quality contact. In this sense, visual signaling becomes a double-edged disruption, creating an unstable perceptual field where symbolic assertion collides with embodied difficulty.

What the Results Tell Us About Behavior and Meaning

The visual data presented across all five charts reveals a central insight: neon gear does not consistently benefit the batter or disadvantage the pitcher. Instead, it introduces a layer of symbolic and sensory instability that reverberates through both sides of the exchange. It does not function as a performance enhancer, but as a cultural irritant—subtle, charged, and unpredictable. What is disrupted is not outcome alone, but rhythm, perception, and decision-making.

Viewed through a symbolic interactionist lens, neon gear operates as a nonverbal act of self-expression within the institutional constraints of Major League Baseball. It alters the perceptual environment in which elite motor behavior unfolds, not through overt distraction, but through symbolic interference that shapes how space and timing are experienced. The data show that pitchers facing neon-wearing batters missed more often and issued more walks, but batters did not respond with higher rates of hard contact. The result is instability, not advantage.

Chart 3 visualized this instability through disorganized pitch dispersion, particularly in vulnerable parts of the strike zone. Chart 4, in contrast, showed a spatial return to order when pitchers faced traditionally dressed batters. This contrast made visible the impact of visual signaling on rhythmic targeting and spatial control. Yet, as Chart 5 showed, hitters in neon gear produced fewer hard-hit balls. The very volatility that disrupted the pitcher’s rhythm also appeared to impair the batter’s ability to capitalize.

This is the defining insight of the study: disruption is mutual. Neon gear distorts the shared perceptual field, creating a loop of instability that affects both command and contact. It is not a tool for competitive gain, but a symbolic variable that subtly recasts the behavioral texture of the game.

Anthropological theory helps surface the deeper implications. For Marcel Mauss, bodily performance is never just functional; it is expressive, learned, and encoded. Tim Ingold emphasizes that perception is not a passive act of seeing, but an embodied process of attunement shaped by movement through space. Sarah Pink shows us that data are not inert facts, but traces of cultural experience. Each of these perspectives reinforces that neon gear is more than gear. It is a visual signal that intervenes in rhythm, ritual, and meaning. In disrupting precision, it remakes the performance.

Looking Ahead: Visual Signaling and the Future of the Game

This study set out to explore whether neon-colored gear in Major League Baseball alters pitcher performance and what that disruption reveals through an anthropological lens. Using simulated data to model symbolic signaling and sensory interference, the research found that neon gear introduces volatility into the pitcher–batter exchange. Rather than creating an edge for one side, the gear fractures rhythm, precision, and focus for both pitcher and batter. Its influence is best understood not as a tool for mechanical advantage, but as a visual and cultural signal that intervenes in perception, embodiment, and ritual. Gear, in this context, operates as a meaning-making object embedded in a highly choreographed system of performance.

What began as a personal interest in gear aesthetics deepened into a broader inquiry into how rhythm, visibility, and symbolic action intersect on the field. As both a returning player and an anthropologist-in-training, I came to see the baseball diamond as more than a site of competition. It became a space of sensory negotiation and ritual communication. Pitchers and batters do not merely react to one another. They participate in a continuous exchange shaped by visual presentation, movement, and anticipation. In this view, the field becomes a layered perceptual environment rather than a neutral arena.

Applied anthropology proves especially valuable in uncovering behavioral patterns that statistics alone cannot explain. It encourages coaches, analysts, and designers to reconsider how visibility, color, and visual rhythm contribute to performance under pressure. What might appear to be style or branding may also be shaping timing, focus, and bodily expression in subtle but measurable ways.

Aesthetic signaling also invites speculation about its future potential. A team adopting all-black gear, for example, could use uniformity and color psychology to project cohesion or intensity. Existing research has linked dark uniforms to increased perceptions of aggression and dominance (Frank & Gilovich, 1988), which in turn influence behavioral expectations and outcomes. In such a scenario, uniform design becomes a form of indirect strategy, not just fashion.

Looking further ahead, future gear designs might unintentionally create visual environments that distort depth perception or disrupt timing. High-contrast patterns, geometric blocking, or nontraditional accessories could create interference zones that subtly affect a pitcher’s spatial calibration. Studies in visual cognition suggest that such illusions are capable of degrading motor performance (Maquestiaux et al., 2022). In a sport where milliseconds define success, even small perceptual shifts could have meaningful consequences. If these effects are already occurring, players and teams may be adapting intuitively, without yet having the language or analytics to describe what they are responding to. Baseball, and perhaps elite sport more broadly, may soon need to consider whether visual signaling is an aesthetic detail or an emerging dimension of strategy.

7. Data Access and Appendix

The simulated dataset used in this study consists of 50 plate appearances, each coded with variables such as batter gear type, pitch type, pitch location accuracy, velocity, hard-hit classification, and final outcome. Although the data was not sourced from live MLB Statcast feeds, it was structured to closely reflect real-world pitcher–batter dynamics, allowing for the exploration of symbolic and behavioral patterns through an anthropological lens.

The complete dataset is available in Excel format and includes full annotations and metadata outlining the coding structure and design rationale. For the sake of transparency and future development, the dataset may also be included as part of supplementary materials or shared in a collaborative portfolio review. A publicly accessible version is provided in the following section via Google Sheets.

The dataset is available here:

References

Baseball Rules Academy. (n.d.-a). 3.03 Player uniforms. Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://baseballrulesacademy.com/official-rule/mlb/3-03-1-11-player-uniforms/

Baseball Rules Academy. (n.d.-b). 3.07 Pitcher's glove. Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://baseballrulesacademy.com/official-rule/mlb/3-07-1-15-pitchers-glove/

Frank, M. G., & Gilovich, T. (1988). The dark side of self- and social perception: Black uniforms and aggression in professional sports. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.74

Ingold, T. (2000). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203466025

Maquestiaux, F., Arexis, M., Chauvel, G., Ladoy, J., Boyer, P., & Mazerolle, M. (2022). Visual illusions influence proceduralized sports performance. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 29, 1490–1497. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-022-02145-6

Mauss, M. (1973). Techniques of the body. Economy and Society, 2(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003

Pink, S. (2021). Doing visual ethnography (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/doing-visual-ethnography/book271555

Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Aldine Publishing. https://www.routledge.com/The-Ritual-Process-Structure-and-Anti-Structure/Turner/p/book/9780202011905

Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management. (2013, November 13). Neon projects elite aura for amateur athletes. https://business.vanderbilt.edu/news/2013/11/13/neon-projects-elite-aura-for-amateur-athletes/

VenuEz. (2023). The role of color psychology in fashionable sportswear design. https://www.venuez.dk/the-role-of-color-psychology-in-fashionable-sportswear-design/